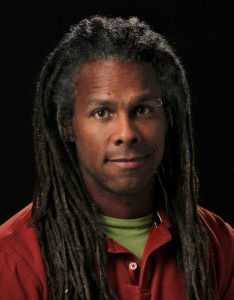

Greg McCreery, 39, has to cobble together several philosophy courses on two campuses each semester to make an average annual salary of $35,000. “There’s always a risk I won’t make enough money” to support his family, he says.

By NANCY McCANN

USFSP Student Reporter

One of the last things college students expect to learn is that their instructor is living below the poverty level.

Or can’t afford to take a modest vacation.

Or is working three jobs.

But that is the reality for many of the temporary, part-time teachers around the country known as adjuncts.

In the Southeast, they are typically paid between $1,800 and $2,700 per course each semester, although some make significantly more, depending on the individual and institution.

Consider the numbers at USF St. Petersburg:

- Almost half of the faculty in 2016 – 128 of the 269 teachers, or 48 percent – were adjuncts. In 2015, it was 138 of the 280 teachers, or 49 percent.

- Adjuncts taught 39 percent of all undergraduate student credit hours and 68 percent of all undergraduate course sections in 2015, according to numbers collected by the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools. In graduate programs, adjuncts taught 25 percent of the courses and credit hours.

- On average, USFSP adjuncts earned around $8,180 per year by teaching about 25 to 30 percent of a full-time load, according to a 2015 university report. The average annual salary for full-time USFSP faculty was $79,496.

Greg McCreery, 39, an adjunct who teaches philosophy on the St. Petersburg and Tampa campuses, said he usually has six classes in the fall, five in the spring and one in the summer. His average annual salary? About $35,000 for a married man with two young children.

A few years ago, he said, he lost health care benefits because he came just short of the required teaching load.

“I’m a full-time teacher who has to grade and take care of students, but every semester I have to find classes to teach,” said McCreery. “There’s always a risk I won’t make enough money or have benefits. We (adjuncts) have no guarantees.”

After years of complaints, some adjuncts like McCreery are beginning to take action.

On April 20, a group representing adjuncts on the three campuses in the USF system – St. Petersburg, Tampa and Sarasota-Manatee – filed a petition to hold a union election sometime in the months ahead.

If a majority of USF adjuncts approve, the Service Employees International Union (SEIU) would become their agent in seeking better pay, benefits and job security.

“Right now, adjunct faculty cannot earn job security, even after many years of dedicated service,” union organizers told USF adjuncts in an email last year.

“Pay is out of step with Florida’s cost of living, there is a ceiling on opportunities for advancement, and it is routinely unclear whether our classes will be offered in the upcoming or subsequent semesters. These working conditions are detrimental to our efforts to teach effectively, to develop as professionals, and to contribute to the intellectual life of our campus communities. Also, these conditions force some of us into poverty, unable to afford our living expenses.”

* * * * * * * * *

Peter Golenbock, 70, a nationally known sports author, acknowledges that he could – and would – teach his classes on sports and American history for free. But he says the campaign to unionize adjunct teachers at USF’s three campuses is a just cause.

Around the country in recent decades, the number of adjuncts has been rising as college administrators seek to hold down costs, including student tuition and fees.

Adjuncts (not including graduate assistants and other non-tenure track employees) now make up more than 40 percent of the faculty in schools across the United States. In 1975, it was 25 percent.

Part-time faculty typically fall into four groups: Graduate students; retired academics and other professionals; people working in government and private business who like to teach on the side; and teachers striving for a career in higher education by piecing together jobs each semester, sometimes at multiple schools.

At USFSP in recent years, adjuncts have included high-profile figures like Melanie Bevan, a former assistant police chief in St. Petersburg who is now police chief in Bradenton; the late Terry Tomalin, the longtime outdoors editor at the Tampa Bay Times; and Fred Bennett, a former Tampa business executive who helped oversee a program linking the College of Education to youngsters at some of St. Petersburg’s struggling elementary schools.

They typify the group of adjuncts who teach for emotional fulfillment and the chance to give back to the community.

“Don’t tell the administration, but I could do this – and would do this – for nothing,” said Peter Golenbock, 70, a nationally known sports author and law school graduate who teaches classes about sports and American history. “These kids are wonderful, and I enjoy the hell out of it.”

But Golenbock was one of the names on a recent email urging fellow adjuncts to support the union campaign.

“Every other type of faculty (at USF) has a union, including teaching assistants,” he said in an interview. “The cause is just and I can’t imagine anyone disagrees with that.”

He said his support for the union drive “simply has to do with fairness” – adjuncts must be able to “make a living” so the best teachers can be hired.

“I’m rooting for ‘em,” said Golenbock.

But for every financially secure adjunct like Golenbock, it seems, there is an adjunct like McCreery, the philosophy teacher on the Tampa and St. Petersburg campuses who is struggling to make a satisfactory income.

“Did you know that a definition of the word “adjunct” is “an inessential part of something”? he asked.

McCreery said he has no interaction with other philosophy professors, and since he must share an office on the Tampa campus with other adjuncts he can’t leave books and other material there to share with students.

“Right now, we (adjuncts) have no voice,” he said. “Everyone else at the university has union representation. It makes sense that full-time professors make higher salaries (than adjuncts), but we deserve more.”

* * * * * * * * *

Adjuncts “are floating out there alone,” says Rebecca Skelton, who teaches art on the St. Petersburg campus.

Some of the adjuncts around the country who struggle to make ends meet consider the growing, low-paid work force a crisis in higher education.

That has helped spur the drive to form unions – a drive that is gaining momentum.

In the last three years, adjuncts at schools like Duke, Georgetown, Tufts and the University of Chicago have joined SEIU, the union says, and adjuncts at more than 50 other schools are considering it.

The union has already had an impact on some campuses.

According to SEIU, the “median pay per course was 25 percent higher for part-time faculty that had union representation.” The union says that part-time faculty at Tufts now make at least $7,300 per course; adjunct pay at George Washington University increased 32 percent in one department with the first union contract; and Antioch adjuncts now have defined workload expectations and protected health care insurance.

In November, part-time faculty at Hillsborough Community College in Tampa voted 2 to 1 to join SEIU. The victory was announced as the first for adjuncts at a public school in the South.

“There are a lot of people who want to get behind” the union drive, says Jeanette Abrahamsen, who teaches broadcast news and beginning reporting on the Tampa campus.

HCC adjuncts are now seeking a collective contract to improve pay and working conditions.

Rebecca Skelton, a USFSP adjunct who teaches art, and Jeanette Abrahamsen, an adjunct who teaches broadcast news and beginning reporting at USF Tampa, were guests this spring on WMNF’s call-in show, “Radioactivity,” to talk up the union.

Abrahamsen, 31, who has a master’s degree in digital journalism and web design from USFSP, said she had met with other adjuncts to talk about banding together.

“It helped us just to meet and talk about it because a lot of times you don’t know a lot of the other adjuncts. We are working at different times and people are driving around to different campuses,” said Abrahamsen. “Once we started talking about it, we realized there are a lot of people who want to get behind this.”

“We are floating out there alone,” Skelton, 64, told The Crow’s Nest. “You can feel from some of the professors that you are not as good as full-time faculty.”

* * * * * * * * *

Adjuncts are “a great resource” who complement full-time faculty well, says College of Business chief Sridhar Sundaram.

At USFSP, the pay for adjuncts is set by the college they teach in – Arts and Sciences, Business, or Education – and the philosophy on utilizing adjuncts seems to vary from college to college and department to department.

For example, adjuncts make up about half the faculty in the Kate Tiedemann College of Business, and exact numbers can vary from semester to semester, according to Dean Sridhar Sundaram.

Because of their expertise in specialized topics outside the university, he said, adjuncts are paid $3,500 to $5,000 per course. They teach 30 percent of the credit hours in the college, he said.

USFSP business adjuncts include professionals working in government, accounting and investment firms, and health services administration.

The majority of core and introductory courses are taught by full-time faculty, while adjuncts teach electives, Sundaram said.

“The spirit of using adjuncts in my college is that we want someone who is an expert in their area,” said Sundaram. “Adjuncts are a great resource to tap into, and they complement full-time faculty well. It would be difficult without them.”

Adjuncts with doctorates make more than those with master’s degrees, says Lisa Starks, chair of the Verbal and Visual Arts Department.

The portrait of an adjunct in the College of Arts and Sciences can be quite different.

In the English program, there are eight full-time faculty and 19 adjuncts, said Lisa Starks, chair of the Verbal and Visual Arts Department.

Adjuncts taught 56 percent of the classes this semester in the English program – 40 percent of the classes on campus and 81 percent online.

The adjuncts with master’s degrees make $2,500 per course per semester, said Starks. Those with doctorates make $3,000.

“It would be wonderful if we could use full-time faculty only, “said Starks. “If the budget allowed, it would be a dream come true.”

Morgan Gresham, the department’s creative writing program coordinator, said the department utilizes guidelines published by the National Council of Teachers of English for the working conditions of adjuncts.

The guidelines include making teaching appointments in a timely manner, providing office space with access to computers and telephones, and including adjuncts in faculty meetings and on committees.

“Many of our adjuncts have been here for years,” said Gresham. “I would love for them to have an opportunity to be full-time.”

One of the two full-time professors added to the department a couple of years ago was an adjunct who was “given the chance to move up,” said Starks.

Starks said she was an adjunct herself “a really long time ago,” teaching five classes in a semester when she was a graduate student. She also taught aerobics and GRE prep.

“We are doing the best we can to make the lives of our faculty and students the best for everyone,” she said.

* * * * * * * * *

Although adjuncts are often described as talented and popular teachers who can bring outside experience and a love of teaching to the classroom, the cost savings may have a downside for students, at least according to one study.

The American Association of University Professors (AAUP), a nonprofit association of academics that strives to maintain quality and preserve academic freedom in higher education, issued a report in 2016 repeating its 2003 conclusion that “the dramatic increase in part-time faculty has created ‘systemic problems for higher education’ that have … diminished student learning.”

The AAUP report says that “while many faculty members serving in part-time positions are well qualified and make extraordinary efforts to overcome their circumstances, researchers have found that having a part-time instructor decreases the likelihood that a student will take subsequent classes in a subject and that instruction by part-time faculty is negatively associated with retention and graduation.”

The report says that “every 10 percent increase in part-time faculty positions at public institutions is associated with a 2.65 percent decline in the institution’s graduation rate.”

Part of the problem, according to AAUP, is that many adjuncts are less available to students than full-time faculty are. The reasons for this include the paradox that adjuncts sometimes teach more courses than full-time faculty due to the low wages they receive per course, they are less integrated into the institution, and they do not have access to as many resources.

AAUP also mentions that adjuncts are assigned to “crowded group offices” or do not have one at all, making it more difficult to meet with students.

A glut of adjuncts diminishes the influence of full-time faculty, says Vincent Tirelli, an adjunct at City University of New York.

Vincent Tirelli, 58, an adjunct for over 25 years who teaches government and politics at the City University of New York, said “one of the most important things research has shown is that students need contact with their professors and their peers.”

Tirelli wrote his doctoral dissertation – “The Invisible Faculty Fight Back” – on what some call “precarious faculty” and was one of the founders in 1998 of the Coalition of Contingent Academic Labor. He said a university with a lot of adjuncts can have consequences for full-time faculty.

“In the past, the idea that our colleges and universities were governed by both the administration and the faculty was a thing – shared governance,” Tirelli wrote in an email to The Crow’s Nest. “Less and less is that the case, and with the growth in the use of part-time faculty the idea is pretty much a joke. Thus, we have the corporate university.”

* * * * * * * * *

What about students – and their parents? After all, they are the consumers at USFSP.

Students sometimes do not know their class is being taught by an adjunct. Some are not even familiar with the term. But interviews suggest they do have opinions on what makes a good teacher.

Take Zack Batdorf, 22, a senior majoring in psychology. Asked if it concerns him that an instructor is not a full-time professor or does not have a doctorate, he said these things don’t matter to him.

“Certainly, for me, it’s the quality of the experience that’s important,” said Batdorf. “How can I relate to the teacher?”

Samantha Ortiz, 18, a freshman majoring in criminology, said she knows exactly what an adjunct is because an “honest and passionate” instructor last semester talked about his financial hardships and explained to her class that adjuncts like himself were “not being treated as equals.”

Ortiz said the instructor “made me think outside the box,” and although he was not available all the time, he “tried to make the most of helping his students.”

“Being a good teacher has to do with how much they involve themselves with you, not their Ph.D. or whether they work full time,” said Krista Evans, 21, a junior in mass communications. “Adjuncts deserve a shot, too.”

Nancy McCann, a graduate student in journalism and media studies, has taught as a graduate assistant and adjunct at USF Tampa and USFSP.

* * * * * * * * *

Information in this article was obtained from the following reports:

“Higher Education at a Crossroads: The Economic Value of Tenure and the Security of the Profession (2015-16),” American Association of University Professors.

https://www.aaup.org

“Statement from the Conference on the Growing Use of Part-time and Adjunct Faculty” and “Position Statement on the Status and Working Conditions of Contingent Faculty,” National Council of Teachers of English.

http://www.ncte.org/positions/workingconditions

“This Was Our Movement in 2016” and “SEIU Contract Highlights: The Union Difference,” Service Employees International Union.

http://www.seiu.org

Dr. Lauren Friedman, Director of Institutional Research, USFSP Office of Academic Affairs, provided data reported to the National Center for Education Statistics through the Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System and the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools.