By Shelby Churchward

Life is hard enough for people who do not have an autoimmune disease, but it becomes even more complicated when you add diabetes to the mix.

Picture this: you and I sit down at a restaurant to eat lunch. You take a sip of your soft drink and munch on some chips while you wait for your tacos to come to the table. The atmosphere is chatty, and the weather is warm but not overbearing. You think nothing of what you are eating and drinking at this moment.

But as I’m sitting next to you, I have already done all the math on what I chose to eat and drink, prepped the insulin that I will need for this meal, and checked to make sure I have enough medication left to handle anything that might occur after the meal.

As a type one diabetic, there is a lot more that goes into simple, everyday tasks that someone without this disease would not even think about.

Type one diabetes is a genetic disorder that can show up in childhood and lasts through the rest of one’s life. Aimee Dougherty, a nurse practitioner at the Wellness Center at the University of South Florida St. Petersburg campus, said is a long-lasting condition “in which your pancreas produces little to no insulin and requires insulin therapy, monitoring blood sugar levels, diet and exercise to maintain normal blood sugar.”

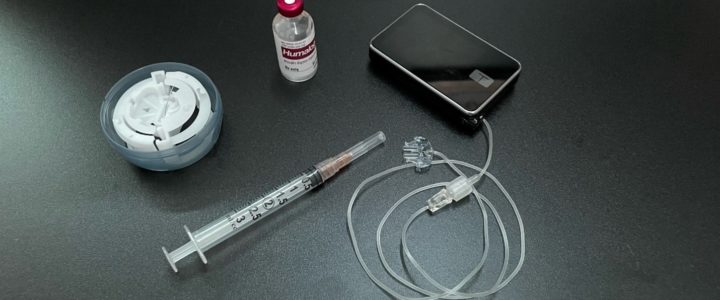

Photo by Shelvy Churchward

I use an insulin pump to help regulate my blood sugar levels instead of the typical needles you might think of. This pump essentially functions as an external pancreas, constantly adjusting the amount of insulin I have on board to maintain blood sugar levels.

Usually, when I tell someone that I have diabetes they assume that I cannot have things like cake or cookies. While that may not be the case, I still find myself avoiding certain foods.

I have stopped drinking juice and soda. I no longer eat sweets or foods that contain a lot of complex carbohydrates purely because I have no desire to deal with the outcome. When I consume those foods, it is difficult to predict what they will do to my blood sugars. So as much as I might enjoy a good PopTart or a Dr. Pepper, I no longer indulge in those things.

My little sister, Marley Churchward, has spent the past 10 years learning how to adjust certain aspects of her life to best adapt to her diabetes.

“I really have to think about how much physical activity has a larger effect on my sugar levels. Plus, the ways my levels being too high or too low can affect how well I make critical thinking decisions. This disease is all about learning from your mistakes. It’s not easy and you can’t let it control you,” Churchward said.

I work hard to maintain good health and appropriate blood sugar levels and I can tell you it is a full-time job. Every time I want to have a slice of cake, I have to figure out how many carbohydrates are in the cake and formulate a math equation to determine how much insulin I need to take. I then have to put that information into my insulin pump to be delivered to my system.

Every night when I lay down to go to sleep, I plug my insulin pump into the charging cord. This means that while the insulin pump is attached to me, I am attached to the charging cord on the wall. I can only roll so far away.

Many others struggle with this disease and the lifelong effects it carries. Many type one diabetics have had the disease for so long that they stop thinking anything about the differences that exist in everyday life. However, there are people who struggle to come to terms with certain areas of it, such as Rob Boehlein, who has been diabetic since he was 5 years old.

“There’s always a looming medical cost that takes a large toll, mentally, on me. Not to mention a feeling of burden that I might put on anyone who would choose to be involved with me. I almost feel like the psychological effects of living with an irreversible disease like this might be the biggest difference,” Boehlein said.

Maintaining a positive mindset is hard even without the added stress that comes along with Diabetes. Despite the challenges, many diabetic college students are making the best of their situations and staying strong.

The best way to take care of yourself as a diabetic living on a college campus is “Stay as active as possible and eat healthy low glycemic foods, stay on top of your labs and medical appointments. If you’re taking medication, take it as directed, do not skip doses or change how it is to be taken,” Dougherty said.

And diabetes among young people is much more common than you might think. Dougherty pointed to the recent National College Health Assessment for USFSP, which found at least 2.1% of students had been diagnosed with diabetes or pre-diabetes/insulin resistance by a doctor.