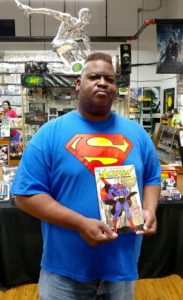

Bryan Sims, shown with issue No. 1,000 of Action Comics, has a 28-box collection of comic books.

By JEFFREY WAITKEVICH

USFSP Student Reporter

ST. PETERSBURG – Bryan Sims was 7 when he rode his bicycle to Haslam’s Book Store in 1976 to buy his first comic book – “The Flash 245.”

Kevin L. Haskins began reading X-Men comic books before he joined the comic book club at Hudson Middle School in Pasco County in the late 1980s.

For Christopher J. Goodwin, it started when he was a boy in St. Petersburg, drawn to the old Aquaman and Iron Fist comics of the 1970s.

Now, the three self-proclaimed comic book geeks have something else in common: They are all officers at the St. Petersburg Police Department.

When they cross paths, they chat about the action heroes in their colorful collections – “a great outlet for stress relief,” said Sims – and plan trips to see action movies.

Their latest group outing? Seeing the newest Marvel film, “Avengers: Infinity War,” which opened April 27.

From modest beginnings in the 1930s, comic books – and they movies they inspire – have become big business in the United States.

Comic book stores abound, and a modest, one-day convention for collectors that began in San Diego in 1970 now has a corporate sounding name – Comic-Con International. It draws more than 130,000 people who pay up to $2,000 to dress up as super heroes and mingle with artists, Hollywood stars and fellow collectors.

Goodwin says he identifies with superheroes’ positive traits.

To some, it may seem curious that police officers – who see plenty of sometimes gritty action in their daily jobs – are drawn to the make-believe world of action figures in comic books and movies.

But Sims, Haskins and Goodwin think it’s perfectly logical.

Haskins, 41, fancies Cyclops’ leadership and ability to balance the egos of the X-Men.

Goodwin, 52, said he identifies with the traits of some superheroes: Batman’s reasoning, Captain America’s patriotism, Black Panther’s pride, Thor’s incredible power and the Punisher’s sense of right and wrong.

As for police officers in comic books, they “are almost always portrayed in the best light and as heroes,” said Sims, 48. “The good ones prevail over corrupt ones.”

Alas, the comic book trio at the Police Department is breaking up. Sims is retiring after 27 years with the department, but the nerdiness will live on.

Sims said he will continue adding to his 28-box collection – that’s thousands of comics – and share his wealth of knowledge with anyone willing to learn.

Meanwhile, Haskins and Goodwin are working to pass their knowledge down the family tree.

Haskins has started teaching his 2-year-old daughter to recognize characters, while Goodwin’s 4-year-old grandson has already selected Hulk as his favorite character.